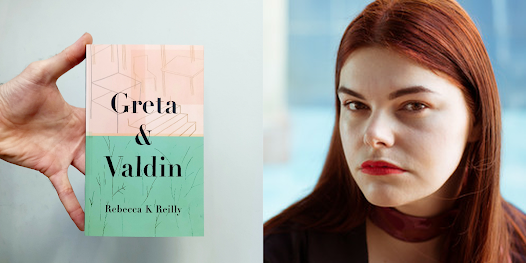

Stella: Greta & Valdin has been a sensation — topping the indie bestseller charts and capturing a rapturous audience. Why do you think it has been so well received?

Rebecca: Oh, I mean, I think only some of a book’s numbers are down to writing. It has to be in the right hands at the right time and have ticked a whole lot of boxes like inoffensive blurb, cover that doesn’t clash in a flat lay, author photo where the writer doesn’t look too furious. Then on top of that you need word of mouth recommendations, so the content of the book has to be okay as well. Here this book has good fortune because it doesn’t really have objectionable content in it, so if the reader enjoys it they can pretty much recommend it freely except to people who are homophobic or have a vested interest in preserving Iberian Spanish. Or people who tend to err on the side of finding any kind of vague angle of intellectualism pretentious and classist, this nerd book is not for them. One of my favourite books is Bear by Marian Engels and I can’t recommend it to many people at all because you have to be chill about what I guess we can call theoretical zoophilia here.

Stella: While reading this, I was actually aware of the balance you strike in keeping the lively energy of the protagonists (and the cityscape they live in — the city is vividly portrayed) front and centre while simultaneously delving into deeper themes on race and gender. Do you think humour is a vital tool in your kete? And where is it most useful or most successfully employed? Can it also, in contrast, obscure the intent of the writer?

Rebecca: I think balance is the key for me here. When I’m editing, I’m mostly thinking about how I can achieve a balance of entertainment and, ugh, pathos I guess? I want to feed the reader the vegetables (the gay agenda) a little bit but I mainly want to do what’s best to make an entertaining story with emotional highs and lows. I think it would be disingenuous to leave out the political realities that people like the characters in the book have to live with, but I’m not, you know, I’m not in the business of achieving social justice through opaque messaging. We don’t need books for that, we have the Instagram explore page.

I guess humour is good when trying to squeeze through material that’s difficult somehow, dense or dull but necessary structurally, or just straight out painful. I am aware that what I’m writing in a manuscript is intended for public consumption so I’m purposefully trying not to obscure my intentions with weird edgy jokes. Sometimes I think of something that would be funny but it’s too much, which I don’t see as self-censorship but rather a form of curation. I save that stuff for my edgy personal associates.

Stella: Love is a central theme to the book, whether that is raw and new or more nuanced and convoluted. At times, your novel seemed to sit alongside a Sally Rooney work, while at other times a classic Austen, Dickens (all those machinations) or a Russian meld of Chekhov and Tolstoy. What do you think?

Rebecca: Ah, I think the book is kind of tricky in this way. It does sit alongside the novels of Sally Rooney, Naoise Dolan, Laura McPhee-Browne and others because in a way, I’m also this kind of writer, I was born at the same time and I’ve spent many years at university and wear midi skirts. But I can’t say that I was influenced by millennial novelists at all, because when I wrote this book I was very out of touch with what was going on culturally with novels. I read all these books after I wrote mine. I think I’m this genre of writer circumstantially, but. . . taller and indigenous and from a different country.

I got an Austen comparison on my original manuscript for this book by the examiner, but I didn’t really know what it meant because I have never read the work of Jane Austen. My grandmother had the BBC adaptation on video and I watched one of the videos, I guess twenty years ago. I’ve never read Dickens either, I just know enough about these things to yell five sisters or Ebenezer when I’m watching The Chase. I’ve never read a Russian novel either, actually. I’ve read Uncle Vanya and The Cherry Tree. I’ve seen a production of The Pōhutukawa Tree.

I think I’ve just always been interested in convoluted plots with many mysterious characters and motives, the first time I was asked to move onto a new project rather than writing one never-ending story was in Year 1 when I filled up a whole exercise book with my story We’re Going to Invercargill, a place I had heard mentioned approximately one time. I think this is maybe what happens when you have an autistic child who likes writing but has no interest in fantasy or science fiction or non-fiction. Just this elaborate take on social realism. I used to play limb centre with my dolls, after going with my dad to pick up a new prosthetic leg once. Now I’m an adult who can invent new people and situations from scratch but would be extremely pressed to make them exist on streets that aren’t real. I’m sorry, I haven’t said anything about love – I like thinking about how love works and how people relate to one another, what sort of forms that can take, how far it can stretch. It’s an interesting area of thought like oceanography or linguistics.

Stella: Your book has a happy ending — mostly. Did you intend this?

Rebecca: The end of the book is definitely the part I’ve had the most negs about (rushed, messy, loses it, but also overly neat, unrealistic, cutesy) but I did intend it to be how it is. I know the author’s intention doesn’t matter and it’s all up to the reader, but here my intention was not to show a happy ending as such, but a not-horrible ending for my two protagonists. You know, in the queer community and in the Māori community we’ve got enough media where something cooked happens to the characters right at the end. This is not a book where people are drowning or going to jail or revealing they’re actually straight-engaged to someone else at the end. My secondary intention was to show that although maybe everything is momentarily fine in the world of the protagonists, they also needed to realise that the world, and even the people closest to them, operate on their own terms without their intervention. I wanted to break from the insularity of the tight first person and show that other stuff was going on and other characters had different viewpoints and other things they were dealing with.

I’m interested in the narrative perspective of Less, by Andrew Sean Greer, where the third-person narrator turns out to be someone in love with the protagonist and A Series of Unfortunate Events where the narrator is in love with someone who turns out to be the deceased mother of the protagonists. I wanted this type of effect as well, for my own Beatrice, a smaller version of it, not directly through narration but an absence of it. From one perspective, this book is a year in the life of a woman who has a lot going on socially and emotionally, but we only ever hear about it from the perspectives of two of her children, one who has no idea what she’s up to and one who seems like he might actually, but he just doesn’t think about it. He’s got a lot on too and has strong reasons for not thinking too much into the affairs of his mother because they affect him too much.

I don’t know, I

think that this thing I’m trying to do is definitely a two-book job and I don’t

regret sowing the seeds into the first book even if I can never be bothered

doing the second one and a fraction of people just think I’m shit at writing

endings. They don’t know what’s in my mind. I’m a real shocker for putting

information for one text in another, I wrote a short story for Starling set

the year before this book and V says that when he turns thirty he’ll simply

stop mentioning his age. Which he does, in Greta & Valdin, he says

that he’s 29 and that it’s his birthday the next month several times in the

first few chapters and then he never mentions it again. I’m just giving away

information at this point because the book came out a year ago next week and I

would like to stop talking about this one soon and move onto the next one, I’m

shit at multi-tasking. Anyway, all the things I’ve done have been worth the

risk, would trade again.

No comments:

Post a Comment