Tuesday 31 January 2017

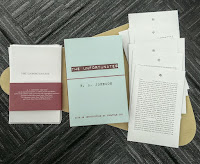

The Unfortunates by B.S. Johnson {Reviewed by THOMAS}

The 27 sections of this novel are not bound together but come in a box so that, apart from the first and last sections, they can be arranged and read in any order. With unselfsparing autobiographical rigour, Johnson (who, ever a provocateur, stated that “telling stories is telling lies”) tells of a journalist who travels to [Nottingham] to report a football match and is constantly put in mind of previous trips to the city to visit a friend who died young of cancer. Memories of Tony and his decline are intruded upon by unbidden memories of a former lover who once accompanied him on a visit. Johnson gives scrupulous attention to how the concrete mundane either ignites emotional significance or provides a respite from (or impediment to) emotional significance when touched by the seemingly haphazard movements of the mind (hence the unbound sections) as it attempts to face but cannot bring itself to face the inevitability of death. “I fail to remember, the mind has fuses.” The Unfortunates is an impressively alert and careful portrayal of memory’s capacities and shortcomings, and an exacting yet moving portrayal of loss.

|

|

Inside the Head of Bruno Schultz by Maxim Biller, with two stories by Bruno Schulz {Reviewed by THOMAS}

During World War 2, the writer and painter Bruno Schulz was kept from the gas chamber by a Gestapo officer who wanted him to complete a mural for his children’s nursery. One day he was shot in the street by another Gestapo officer while returning to the ghetto with a loaf of bread. In this little book, Maxim Biller imagines a time just before the German invasion of Poland, with Schulz hidden from fear in his cellar and writing a letter to Thomas Mann, imploring his help and warning him that Mann’s sinister double, or at least someone claiming to be Mann, is present in Schulz’s town of Drohobycz, presaging in many ways the coming German invasion. Biller’s Schulz is having trouble concentrating and in making his message to Mann clear, and has to restart many times, each attempt being less successful than the last. The letters are invaded by fears and memories, or the doubles or stand-ins for fears and memories, and it soon becomes unclear which elements belong to the description of Schulz writing, which to the letter he is writing and which exist only in the head of Schulz and not in what he is writing or in the world in which he sits and writes. Even if it all only exists in Schulz’s head, and of course it does (he is alone), this three-fold distinction, or rather the inability (of Schulz and of the reader) to make this three-fold distinction remains. Biller’s text is followed by two of the actual Schulz’s most representative stories, ‘Birds’ (about a melancholic father’s increasing over-identification with birds) and ‘Cinnamon Shops’ (concerning the dissolution of the actual city into one built of dreams and memories as a boy is sent home from the theatre to fetch his father’s wallet). There is certainly something of Kafka in Schultz’s narratorial relinquishment of initiative to a less-than-conscious weight that presses against the text from below (or within (or wherever)), but Schulz has a wistfulness that gives his writing a flavour all of its own. |

|

City of Lions by Josef Wittlin and Philippe Sands {Reviewed by THOMAS}

The city known variously in history as Lviv, Lwow, Lemberg, לעמבערג and Leopolis in eastern central Europe was once a city where cultures and ethnicities (Jewish, Polish, Ukranian, Austrian) met and enriched each other, but, in the twentieth century, it became a city in which cultures and ethnicities obliterated each other. In the first half of this book, 'My Lwow', Josef Wittlin, looking back from exile in the 1940s, celebrates the rich texture of the city in which he grew up. Lying on the crossroads between East and West, North and South, Lwow was a melting-pot of buoyant and diverse traditions. Reading Wittlin's descriptions of the streets and life of the city reminds me of nothing so much as of The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz (who lived and was killed in Drohobycz, about an hour from Lwow). Although the shadows of the events of WW2 lie across Wittlin's text, his memories of the cosmopolitan city are all the more poignant for his saying little of them. “All memories lead to the graveyard,” he says, though. The second half of the book, 'My Lviv', is written by human rights lawyer Philippe Sands, who travelled to Lviv, now in the Ukraine, in the last several years, partly to learn more about his grandfather, who had lived there in the early twentieth century, but spoke little of that phase of his life, and partly to research his remarkable book, East West Street: On the origins of genocide and crimes against humanity – terms coined by Lvovians Rafael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht – which won the 2016 Baillie Gifford Prize for Nonfiction. His is a mission to connect history to its locations, but he finds that everywhere, although the old Lwow physically persists, the stories that should give those places meaning are forgotten or suppressed. “Wittlin believes that memory 'falsifies everything', but surely imagination of the unknown is an even greater falsifier,” Sands writes. History must be multivocal to avoid authoritarianism. Sands finds and visits the site of the mass grave which holds the remains of the majority of the Lvovian Jewish population, killed when the city came under Nazi control in WW2. The city now being almost entirely monocultural, Sands reports the unchallenged ease with which some Ukranian nationalists assume the trappings and ideologies once stamped on the city by Nazism. But what should be preserved, the rights of the individual or the identity of the group? |

|

The Babysitter at Rest by Jen George

The self-obsession bordering on narcissism which passes for purpose among thirty-something arty types who have not yet succumbed to despair or parenthood or both is here forensically explored in five longish stories with protagonists for whom the aspirations towards “self-fulfillment” (admit you also have these tendencies) are proving insufficiently resilient to masquerade as anything other than the self-indulgence tempered only by ennui that they always were (admit you also suffer from this). Maturing may be a liminal process but every doorstep is also a place to trip, and George's stories, although they suffer on occasion from the self-indulgence one would expect from their subject matter, exhibit the sort of stunned lyricism that results when your head hits the floor in mid-sentence (test this yourself). “Your life may fall apart may fall apart around you while you're putting on the act of radiating positivity, but you will not realise it for some time,” says The Guide in the story 'Guidance/The Party'.

{THOMAS}

|

| The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge {Reviewed by STELLA} Faith and her family have shipped out from England to a remote island to escape scandal. On arriving at the island, Faith discovers that her beloved father, a respected minister with an interest in the sciences (evolution, creation and anthropology), has laid himself bare for ridicule. Not long after Faith takes a mysterious trip with her distracted father to hide a strange plant, he is found dead. Faith believes he has been murdered and that somehow this is tied to the plant. As she delves into his papers and journals she discovers the plant is a ‘lie tree’ that supposedly flourishes and bears a fruit when fed a lie. The fruits when eaten will give the recipient the truth. Faith sets out to discover who is behind her father's death and to understand the obsessive behaviour of her father by using the strange properties of this malign plant to seek the truth. Intriguing.The Lie Tree won the Costa Book of the Year in 2015, and recently this special edition was produced with illustrations by Chris Riddell. |

|

|

Saturday 28 January 2017

BOOK OF THE WEEK! We will be featuring books we think are especially deserving of your attention. Come into the shop or visit our website to learn more about the book, the author and content, and to get yourself copy to read!

This coming week's book is Solar Bones by Mike McCormack, the winner of the 2016 Goldsmiths Prize for "extending the possibilities of the novel form".

>> Read Thomas's review

>> Watch this interview

>> Read this review at The Guardian

>> Find our how a single-sentence novel won a major prize

>> Visit Tramp Press, the tiny but wonderful Irish independent publisher who published the book

>> Hear McCormack reading from the novel

>> His 2005 novel Notes from a Coma was described as "the greatest Irish novel of the decade" by The Irish Times

This coming week's book is Solar Bones by Mike McCormack, the winner of the 2016 Goldsmiths Prize for "extending the possibilities of the novel form".

>> Read Thomas's review

>> Watch this interview

>> Read this review at The Guardian

>> Find our how a single-sentence novel won a major prize

>> Visit Tramp Press, the tiny but wonderful Irish independent publisher who published the book

>> Hear McCormack reading from the novel

>> His 2005 novel Notes from a Coma was described as "the greatest Irish novel of the decade" by The Irish Times

Friday 27 January 2017

Just in! Mimicry journal #2 aims "to make New Zealand art and poetry cool again!" Including work by Chris Tse and Claudia Jardine, this lively journal is an organ of New Zealand's literary new wave.

Come and pick up a copy, or click through to our website to read the full list of contributors.

Thursday 26 January 2017

Featured publisher: FITZCARRALDO EDITIONS

Fitzcarraldo Editions is an exciting independent publisher of contemporary fiction (blue covers) and long-form essays (cream). We have the following titles currently in stock (click through for more information and reviews, and to purchase from our website):

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

Always hinting at experience just beyond the reach of language, Bennett's remarkable book is impelled by the rigours of noticing. Her unsparingly acute observations of the usually unacknowledged or unacknowledgeable motivations, urges and responses that underlie human interaction intimate the anxiety which all human activity is designed to conceal.

Always hinting at experience just beyond the reach of language, Bennett's remarkable book is impelled by the rigours of noticing. Her unsparingly acute observations of the usually unacknowledged or unacknowledgeable motivations, urges and responses that underlie human interaction intimate the anxiety which all human activity is designed to conceal.

Nicotine by Gregor Hens

What Thomas de Quincey is to opium, Gregor Hens is to nicotine, the most ordinary of drugs. Whatever your relationship with nicotine, you will find Hens’s rigorous self-examination and ability to recreate the subtleties of his experiences insightful.

What Thomas de Quincey is to opium, Gregor Hens is to nicotine, the most ordinary of drugs. Whatever your relationship with nicotine, you will find Hens’s rigorous self-examination and ability to recreate the subtleties of his experiences insightful.

Counternarratives by John Keene

"A kind of literary counterarchaeology, a series of fictions that challenge our notion of what constitutes 'real' or 'accurate' history. His writing is at turns playful and erudite, lyric and coldly diagnostic, but always completely absorbing. Counternarratives could easily be compared to Borges or Bolano, Calvino or Kis." - Jess Row

"A kind of literary counterarchaeology, a series of fictions that challenge our notion of what constitutes 'real' or 'accurate' history. His writing is at turns playful and erudite, lyric and coldly diagnostic, but always completely absorbing. Counternarratives could easily be compared to Borges or Bolano, Calvino or Kis." - Jess Row

Pretentiousness, Why it matters by Dan Fox

"A lucid and impassioned defence of thinking, creating and, ultimately, living in a world increasingly dominated by the massed forces of social and intellectual conservatism." - Tom McCarthy

>> Meet Dan Fox.

"A lucid and impassioned defence of thinking, creating and, ultimately, living in a world increasingly dominated by the massed forces of social and intellectual conservatism." - Tom McCarthy

>> Meet Dan Fox.

A Primer for Cadavers by Ed Atkins

"Atkins’ writing spores from the body, scraping through life matter’s nervous stuff, leaving us agitated and eager. What’s appealed to us is an odd mix of mimetic futures. Cancer exists, tattoos, squids, and kissing exist – all felt in the mouth as pulsing questions." — Holly Pester

"Discomfited by being a seer as much as an elective mute, Ed Atkins, with his mind on our crotch, careens between plainsong and unrequited romantic muttering. Alert to galactic signals from some unfathomable pre-human history, vexed by a potentially inhuman future, all the while tracking our desperate right now, he do masculinity in different voices – and everything in the vicinity shimmers, ominously." — Bruce Hainley

"Atkins’ writing spores from the body, scraping through life matter’s nervous stuff, leaving us agitated and eager. What’s appealed to us is an odd mix of mimetic futures. Cancer exists, tattoos, squids, and kissing exist – all felt in the mouth as pulsing questions." — Holly Pester

"Discomfited by being a seer as much as an elective mute, Ed Atkins, with his mind on our crotch, careens between plainsong and unrequited romantic muttering. Alert to galactic signals from some unfathomable pre-human history, vexed by a potentially inhuman future, all the while tracking our desperate right now, he do masculinity in different voices – and everything in the vicinity shimmers, ominously." — Bruce Hainley

Notes on Suicide by Simon Critchley

Whether life is worth living or not is not something that can be philosophically contested, but, if it is not worth living, whether suicide is justifiable and well as understandable is perhaps open to examination. Critchley interrogates the standard arguments against suicide and finds them unsupportable. If there is an argument against suicide it is not that life is worth living, but a general one against the possessive individualism upon which our culture, and indeed modern consciousness, depends.

Whether life is worth living or not is not something that can be philosophically contested, but, if it is not worth living, whether suicide is justifiable and well as understandable is perhaps open to examination. Critchley interrogates the standard arguments against suicide and finds them unsupportable. If there is an argument against suicide it is not that life is worth living, but a general one against the possessive individualism upon which our culture, and indeed modern consciousness, depends.

Zone by Mathias Enard

"An ambitious study of twentieth century conflict and disaster. Enard does for the comma in Zone what Eimear McBride did for the full stop in A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, and just as McBride brought her writing a raw intensity and immediacy, Enard brings to his a similarly fierce political engagements and moral authority. Enard’s novel is to be seen within a tradition of French avant-garde writing. The result is a modern masterpiece." — David Collard, Times Literary Supplement

"An ambitious study of twentieth century conflict and disaster. Enard does for the comma in Zone what Eimear McBride did for the full stop in A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, and just as McBride brought her writing a raw intensity and immediacy, Enard brings to his a similarly fierce political engagements and moral authority. Enard’s novel is to be seen within a tradition of French avant-garde writing. The result is a modern masterpiece." — David Collard, Times Literary Supplement

On Immunity by Eula Biss

Weaving her personal experiences with an exploration of classical and contemporary literature, Biss considers what vaccines, and the debate around them, mean for her own child, her immediate community and the wider world. On Immunity is an inoculation against our fear and a moving account of how we are all interconnected;our bodies and our fates.

Weaving her personal experiences with an exploration of classical and contemporary literature, Biss considers what vaccines, and the debate around them, mean for her own child, her immediate community and the wider world. On Immunity is an inoculation against our fear and a moving account of how we are all interconnected;our bodies and our fates.

My Documents by Alejandro Zambra

Whether chronicling the attempts of a migraine-afflicted writer to quit smoking or the loneliness of the call-centre worker, the life of a personal computer or the return of a mercurial godson, this collection of stories evokes the disenchantments of youth and the disillusions of maturity in a Chilean society still troubled by its recent past. "Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents is also his best: an eclectic, disconcerting, at times harrowing read. His voice is unique, honest and raw, and there is poetry on every page. Zambra’s fiction doubles as a kind of personal history, full of anguish, humour and verve. A truly beautiful book." — Daniel Alarcón

Whether chronicling the attempts of a migraine-afflicted writer to quit smoking or the loneliness of the call-centre worker, the life of a personal computer or the return of a mercurial godson, this collection of stories evokes the disenchantments of youth and the disillusions of maturity in a Chilean society still troubled by its recent past. "Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents is also his best: an eclectic, disconcerting, at times harrowing read. His voice is unique, honest and raw, and there is poetry on every page. Zambra’s fiction doubles as a kind of personal history, full of anguish, humour and verve. A truly beautiful book." — Daniel Alarcón

Tuesday 24 January 2017

Sunday 22 January 2017

Late nights 1/7. We are open every Thursday until 7:30. Drop in for some relaxed browsing and conversations about books! This Thursday is also the monthly Late Night on Hardy, so there'll be a string of shops on Hardy Street for you to visit, too.

Late nights 1/7. We are open every Thursday until 7:30. Drop in for some relaxed browsing and conversations about books! This Thursday is also the monthly Late Night on Hardy, so there'll be a string of shops on Hardy Street for you to visit, too.  |

|

| From jigsaws to masks! Masks in the Forest by Laurent Moreau is a story told with masks. The hunter is entering the forest, feeling confident and sure of his ability to ensnare an animal or two. Little known to him, the animals and forest creatures are well aware of his intentions and ready to counter him. The reader of the story can help too! Pop out the face masks and join in with the story. This is a simple story which children can engage with, becoming the characters in the book by donning a mask or two. Plenty of fun and a happy ending too! The illustrations are attractive and the combination of animals - tiger, monkey, deer - and mythical forest creatures - giant, elf - give an added dimension to the story-telling. With nine masks in total this could make a lovely gift for a family, or group of children where new stories can be told as well as the author’s own. {Review by STELLA} |

| Cloth Lullaby is a beautifully illustrated children’s book about the artist Louise Bourgeois, outlining her early connection with textiles via her family’s work as tapestry restorers for generations in France, her early connection with nature, and her path to becoming an artist. While studying mathematics in Paris, Louise’s mother dies and Louise abandons her studies and begins her work as a painter and sculptor - a homage to her mother. The giant spiders she produced are the weavers of webs, and constant repairers. Louise marries and moves to New York, continuing her work in the moments between family and scratching out a living, and builds a dossier of work, fairly much in obscurity. It was not until she was in her 70's that a retrospective exhibition acknowledged her importance as an accomplished and influential artist. Another current publication is Intimate Geometries: The life and work of Louise Bourgeios by critic and curator Robert Storr. This is a comprehensive, insightful and generously illustrated book. {Review by STELLA} |

| This is the Place to Be by Lara Pawson {Reviewed by THOMAS} What do you report when you become uncertain of the facts, of the notion of truth and of the purpose of writing? What can you understand of yourself when you are uncertain how or if your memories can be correlated with known 'facts'? Is your idea of yourself anything other than the sum of your memories? Lara Pawson was for some years a journalist for the BBC and other media during the civil wars in Angola, and on the Ivory Coast. In this book, her experiences of societies in trauma, and her idealism for making the 'truth' known, are fragmented (as memory is always fragmented) and mixed with memory fragments of her childhood and of her relationships with the various people she encountered before, during and after the period of heightened awareness provided by war. It is this intermeshing of shared and personal perspectives, sometimes reinforcing and sometimes contradicting each other, always crossing over and back over the rift that separates the individual and her world, that makes this book such a fascinating description of a life. By constantly looking outwards, Pawson has conjured a portrait of the person who looks outwards, and a remarkable depiction of the act of looking outwards. Every word contributes to this pointillist self-portrait, and the reader hangs therefore on every word. |

| Is That Kafka? 99 Finds by Reiner Stach {Reviewed by THOMAS} Franz Kafka was an exceptional writer, not just in quality but in his qualities. He was also an exception to much of what has been thought of him since, or, rather, both as a writer and a person, he is compounded from exceptions, both to his literary and social milieu and to his own psychology. Not only that, he was an exception to those exceptions. Reiner Stach has written an exhaustive three-volume biography of Kafka, and, while doing so, he has collected these 99 snippets which, published together, display the broader Kafka behind the cliché and are a corrective to conceptions of ‘the Kafkaesque’ which often distort approaches to his works. Kafka never lied but he did cheat in an exam, he liked to drink beer, he followed a fitness regime, he made presents for children, he devised, with his friend Max Brod, a series of on-the-cheap travel guides, he loved slapstick and he liked to be called Frank. Stach also provides a couple of plausible Kafka sightings in contemporary crowd photographs. Is that Kafka? Quite possibly, yes. |

The Childhood of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee {Reviewed by THOMAS} A man arrives, with a new name, Simón, and with no memories of his previous life, in a country whose residents have all, like him, arrived there at some time, shedding their histories and learning a new language, a flat ‘Spanish’, which they use without irony or ambiguity. Existence in Novilla, like Coetzee’s writing, is spare, and abraded of connotation; things have no significance beyond their purpose. The society is founded on good will, respect and the meeting of everyone’s needs; there is enough but no more: no excess, no passion, no longing, no dissatisfaction. Is this the best of all possible worlds? Perhaps Simón has not been washed sufficiently ‘clean’ in his passage to the new life: he feels that human nature requires more intensity than Novilla provides. He brings with him a young boy, ‘David’, who has lost his papers, and who Simon has promised to reunite with his mother. Simon ‘recognises’ David’s mother as the implausible Inès, and hands both the boy and his apartment over to her. Inès infantilises David, and, when he is to be sent to an institution because he cannot/will not accept the basic assumptions of commonality, such as the symbolic assumptions of language and numbers, Simón and Ines flee with him into the hinterland, where reality is even ‘thinner’ than in Novilla and David exhibits disturbingly messianic qualities as they head towards a ‘new life’. Philosophical and ethical questions are raised throughout the book, which turns its back on the possibility of answers, making the whole thing a sort of opaque allegory without any stable referent. In its refusal to satisfy the reader or to be ‘about’ anything (other than itself), whilst engaging our faculties of thinking and feeling, the book, with all its unsettlingly arbitrary developments, inconsistencies and uncertainties, its ambivalences of clutching and relinquishment, resembles ‘real life’ more than most fiction (which is predicated upon the largely unexamined abstractions we construct to ‘pre-package’ and mediate our experiences). At it core, though, this book explores the problematics of fiction-making: characters are suddenly brought into existence by an author in a world which contains only that which the author has created by naming. The characters are entirely subject to the author's will yet struggle, through exerting themselves upon the author, to effect some sort of autonomy. Coetzee is a writer of great weight and precision, and here he continues to push at the edges of his territory. This book has just been followed by The Schooldays of Jesus, which continues the themes explored in this book. |

The Third Policeman by Flann O'Brien

The Third Policeman by Flann O'Brien[Long review:] “Bottomless wonders spring from simple rules repeated without end,” said the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot. This very enjoyable comic novel reveals that, when irreverently applied to science and metaphysics, this observation could just as easily read “bottomless absurdities” or “bottomless horrors” (mind you, Mandelbrot’s fractal theory ‘proves’ that the coastline of any island is infinitely long, which is at once absurd, horrible and true). Falling somewhere in the triangle between Alice in Wonderland, Waiting for Godot and The Exploits and Opinions of Dr Faustroll, ‘Pataphysician, The Third Policeman tells of a chain of events triggered by a murder committed by the narrator (a scholar of the eccentric philosopher de Selby), his visit to a rural police station in a strangely altered bucolic Ireland, and his encounter with two singular policemen who introduce him to such wonders as a spear so sharp it draws blood some distance beyond its visible point, the base substance omnium that is manifest in any form, and an atomic theory that explains the slow transformation of humans into bicycles (and vice-versa) due to rough roads insufficiently maintained by the County Council. All of this (not to mention the crazed inventiveness of Sergeant Pluck’s diction) is a lot of fun if having the rug whipped out from under your feet only to discover that there is no floor beneath is your idea of fun. I have been haunted for years by the scene in which Policeman MacCruiskeen pulls out smaller and smaller boxes from inside each other far into the infravisible, and works on crafting a yet smaller box only to lose it on the floor and have it found by chance by a character named Gilhaney who was only pretending to find it.

[Short review:] It's about a bicycle.

{THOMAS}

Monday 16 January 2017

SOME RECENT BOOKS ON RUSSIAN HISTORY

Second-Hand Time: The last of the Soviets, An oral history by Svetlana Alexievich

A quite remarkable collection of voices by the Nobel Prize-winner in literature, charting the disintegration of the USSR through the experiences of ordinary people, and intimating the kind of riven social terrain upon which any new society must be built.

Where the Jews Aren't: The sad and absurd story of Birobidzhan, Russia's Jewish autonomous region by Masha Gessen

In 1929, with the support of Jewish Communist intellectuals and Yiddishists, preparations were made to establish a Jewish homeland in Russia's Far East (no, this book was not written by Michael Chabon!), and tens of thousands of Soviet and international Jews moved there. With Stalin's purges, the idea fell from favour and the settlers were unsupported. Another influx following World War 2 increased their numbers, but, being easily identified, the Birobidzhanians were increasingly subjected to persecution. An interesting sidelight on Soviet history.

Lenin on the Train by Catherine Merridale

In an attempt to provoke a political crisis in Russia that would take them out of World War 1, the German command 'enabled' Lenin's return by train from exile in Switzerland. Merridale's very readable book traces the journey, the personalities on the sealed train (in which the Germans and the Russians were divided by a chalk line across the middle of the carriage), the struggle between the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks for supremacy in Russia, and the new path taken by Russian and world politics as a result of that journey.

The Diary of a Gulag Prison Guard by Ivan Chistyakov

Astonishing and compelling, this book reproduces a first-hand account of the miseries and rigours of life in a Soviet prison camp, as observed by a senior guard at the Baikal Amur Corrective Labour Camp (Bamlag) in 1935-36.

The Soviet Century by Moshe Lewin

“Probably no other Western historian of the USSR combines Moshe Lewin’s personal experience of living with Russians from Stalin’s day—as a young wartime soldier—to the post-communist era, with so profound a familiarity with the archives and the literature of the Soviet era. His reflections on the “Soviet Century” are an important contribution to emancipating Soviet history from the ideological heritage of the last century and should be essential reading for all who wish to understand it.” – Eric Hobsbawm

How did a group of professors, idealists and entrepreneurs create an intellectual pressure-cooker that made them the envy of the scientific world? And how did Stalin's megalomania and insecurity derail the great experiment in 'rational' government? "A dazzling, often astonishing prism through which to view the Soviet experiment." — Peter Pomeranzev

Sunday 15 January 2017

Give the gift of reading! (or keep it for yourself). Why not let us choose you (or the person of your choice) a book a month on our VOLUME SUBSCRIPTION scheme? Each month we will select a book we think you'll love and have it ready to collect (or send it anywhere to you or to that person of your choice). Click through to our website to see the various options for customising subscriptions!

Give the gift of reading! (or keep it for yourself). Why not let us choose you (or the person of your choice) a book a month on our VOLUME SUBSCRIPTION scheme? Each month we will select a book we think you'll love and have it ready to collect (or send it anywhere to you or to that person of your choice). Click through to our website to see the various options for customising subscriptions!

SHIFTS OF TONGUE. Come and hear Harry Ricketts, Ruth Allison, Cliff Fell and Lindsay Pope reading a selection of poems by Rachel Bush (1941-2016), and some of their own work, too. VOLUME, 15 Church Street, Nelson. Sunday 5 February, 4 PM. Rachel's book Thought Horses was recently long-listed for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

|

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)